This text addresses the questions raised by instructors during a recent training session regarding the use of tourniquets to prevent crush syndrome, also known as prolonged compression syndrome, in the management of crush injuries. A review of the literature on this topic allows us to discuss the use of tourniquets beyond their traditional application, which is primarily the control of life-threatening bleeding. This aspect remains the main focus of our SIRIUS training sessions, but it is also useful to know other potential indications for tourniquet use in specific circumstances.

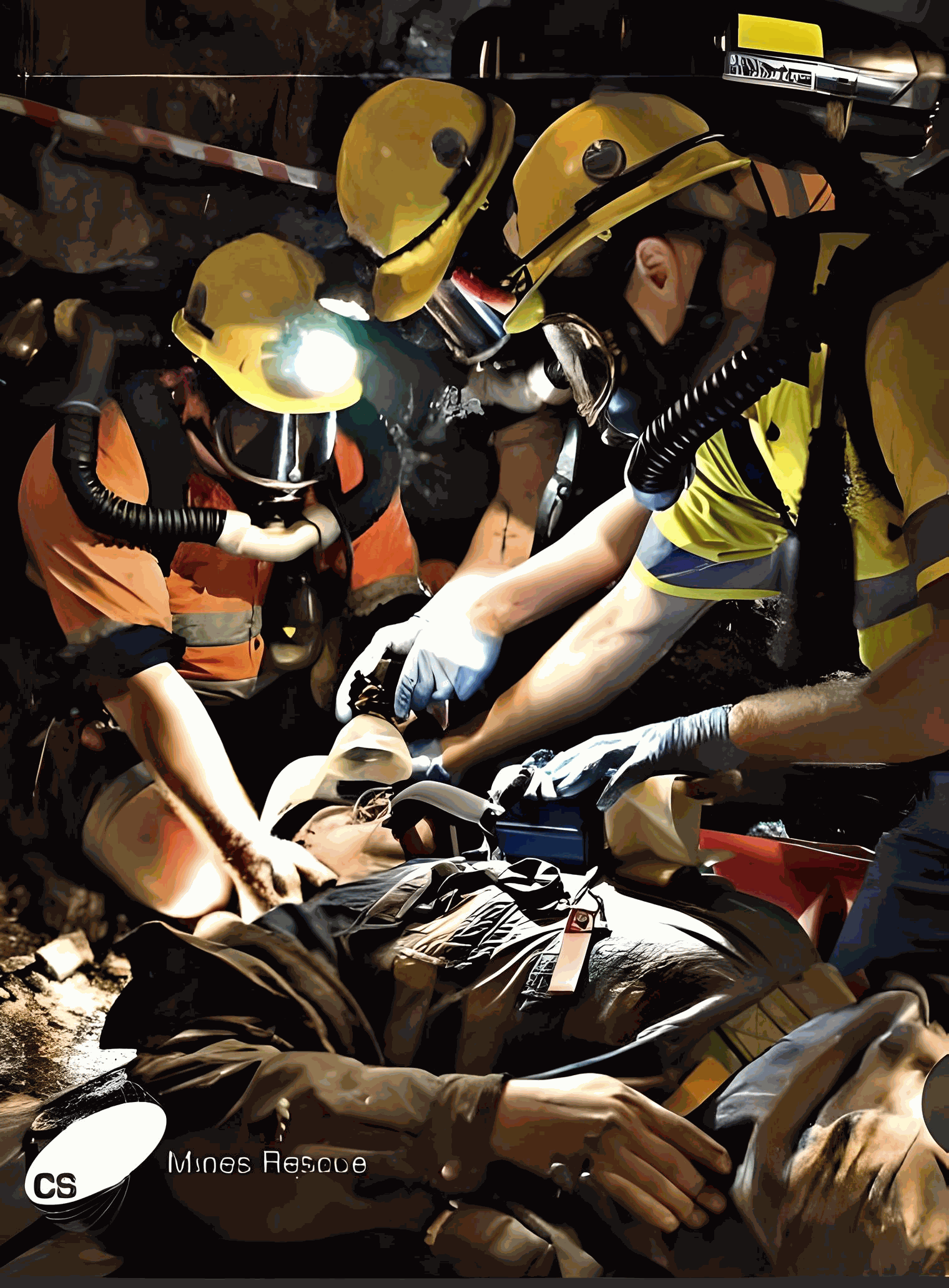

Let's first define what a crush injury is: such an injury or prolonged compression occurs when a significant and continuous force is applied to a part of the body, leading to the crushing of tissues. These injuries are common in industrial accidents, building collapses, road accidents, and during natural disasters.

They involve the compression of muscles, blood vessels, and soft tissues, causing an interruption of blood flow and hypoxia (lack of oxygen) in the affected tissues. The release of pressure can cause a massive release of toxins and metabolic products into the bloodstream.

Although there is no strict duration criterion to define a crush injury, compression of more than an hour is generally considered capable of leading to severe complications. The severity depends on several factors, including the intensity of the applied force, the duration of the compression, the extent of the affected body area, and the presence of aggravating conditions such as hypothermia or hypovolemia, as well as other comorbidities (for example, diabetes).

The most common complications of crush injuries include:

Crushing syndrome: The most serious complication, which can lead to acute kidney failure due to myoglobinuria (presence of myoglobin in the urine), resulting from rhabdomyolysis (destruction of muscle cells).

Compartment syndrome: An increase in pressure within a closed muscle compartment can compromise circulation and may require emergency surgical intervention (fasciotomy) to prevent permanent damage.

Hypovolemia: The loss of fluid in injured tissues can cause a decrease in circulating blood volume, risking hypovolemic shock.

Hyperkalemia: The release of potassium from damaged muscle cells can induce hyperkalemia, which is dangerous due to its effects on the heart.

Metabolic acidosis: The accumulation of acids in the blood following tissue ischemia and rhabdomyolysis can lead to metabolic acidosis.

Immediate and effective management of crush injuries is essential to minimize complications and improve recovery chances. This includes rapid pressure release, hydration to promote diuresis, and close monitoring of renal functions and electrolyte balances.

The use of a tourniquet before releasing compression, with the aim of preventing crush syndrome, is recommended by some organizations, but its specific application for this indication is more controversial and less evidence-based, due to the lack of extensive scientific studies on the subject.

By examining established protocols and emerging discussions on the use of tourniquets in crush injuries, this summary aims to provide you with the necessary knowledge for a better understanding of its use in this type of injury.

This recommendation goes beyond the scope of a 20 or even 40-hour training session but could prove relevant for first responders, as well as to address any potential questions your students may have on the subject.

This recommendation goes beyond the scope of a 20 or even 40-hour training session but could prove relevant for first responders, as well as to address any potential questions your students may have on the subject.

The main teaching of tourniquet use in SIRIUS training remains its use to stop massive bleeding that endangers the patient's life.

General recommendations for the use of tourniquets in preventing crush syndrome (especially in remote settings):

Consider tourniquet application only in specific situations:

Life-Threatening Bleeding: Apply a tourniquet when there is life-threatening bleeding from a limb before or immediately after removing the crushing force.

Extrication Delays: In cases of prolonged extrication lasting more than2 hours or even several hours, where limb ischemia is likely, consider, under medical recommendation, the use of a tourniquet to prevent reperfusion injuries.

Risk-Benefit Assessment: Weigh the potential benefits (such as preventing cardiac arrest) in cases of severe crush injuries, against the risks to the limb when deciding to apply a tourniquet.

Training and Preparedness: Ensure that responders are adequately trained in tourniquet application and understand the context-specific considerations.

Monitoring and Reassessment: Continuously monitor the victim's condition and reassess the need for tourniquet use during transport or in remote settings.

Some articles related to the subject:

A. Crush syndrome: a review for prehospital providers and emergency clinicians(Usuda et al., 2023)

Main conclusions:

1. The importance of immediate treatment initiation: The article emphasizes that starting treatment immediately is the most important factor in reducing mortality associated with crush syndrome (CS) in disaster situations. Early aggressive resuscitation is recommended in prehospital settings, ideally even before extraction, to reduce complications from CS.

2. Challenges in large-scale disasters: In the context of large-scale natural disasters, diagnosing CS and starting treatments such as the continuous administration of large amounts of fluid, diuresis, and hemodialysis on time can be difficult. This challenge may lead to delayed diagnosis and high on-site mortality from CS.

3. Use of tourniquets: The article discusses the controversial nature of using tourniquets to prevent CS before extraction. It mentions that although tourniquet application is not widely recommended to prevent CS, it is strongly recommended in prehospital settings for severe crush injuries. It also mentions a reported case where prehospital tourniquet application was used to delay reperfusion injury after a crush injury, resulting in reduced morbidity and complete limb salvage.

4. Treatment and prognosis: Patient outcomes can be optimized by ensuring that prehospital care providers and emergency clinicians maintain a comprehensive understanding of CS. With recent technological and surgical developments, the field is expected to see significant advances in the coming years, highlighting the importance of ongoing research in managing CS and the potential role of tourniquets.

B. "In adults with suspected crush injury, does the use of tourniquet reduce mortality?"

Main conclusions of the document:

Toxin Limitation: Research suggests it would hypothetically make sense to contain the toxins within the crushed limb until the side effects can be better managed in a hospital setting, due to the potential for rapid patient deterioration due to hyperkalemia.

Tourniquet Side Effects: The side effects associated with the use of tourniquets are considered a significant factor why this management strategy is not routinely used today. However, the document suggests that these side effects are outdated and overstated. In the case of a patient with crush syndrome and prolonged extrication, the potential benefits of reducing negative outcomes, including cardiac arrest upon release, likely outweigh any threat to the limb.

Future Research Needed: Further research, ideally in the form of randomized controlled trials, is necessary to fully assess the risks and benefits of using tourniquets in this context. However, the feasibility of such studies would be challenging due to the low incidence of crush injuries, especially in developed countries.

Amputation: No study has examined amputation as a prophylactic measure to prevent reperfusion in the prehospital setting. Amputations should not be performed to prevent crush syndrome, but only as a last resort if the limb is not salvageable or if it is necessary for rapid extraction if the patient's safety is at imminent risk.

Main Conclusions

There are no published articles collecting objective data to support or refute the use of tourniquets to delay reperfusion and the subsequent side effects. The only available data come from individual case reports. Therefore, the use of tourniquets in the prehospital management of patients suffering from a crush injury cannot be routinely recommended. The collection of objective data is necessary to facilitate a better understanding of the risks and benefits of tourniquets in patients with crush injuries and, subsequently, to discuss their potential use. Amputation is not advocated prophylactically to prevent reperfusion, only as a last resort if the patient's safety is at imminent risk.

In cases of crush syndrome, where a victim has undergone prolonged extrication and limb ischemia, the potential benefit of using a tourniquet to reduce negative outcomes upon release likely outweighs any threat to the limb and should be considered with medical advice.

C. Crush injury and syndrome: A review for emergency clinicians

Summary of recommendations regarding tourniquet use:

The placement of a tourniquet before extrication remains controversial.

The Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) of the Joint Trauma System (JTS) states that if fluid resuscitation and monitoring are not immediately available, a tourniquet may be placed on the affected extremity before extrication if the entrapment time has exceeded 2 hours to help prevent crush syndrome.

The best way to achieve this is to apply two tourniquets side by side, proximal to the injury, immediately before extrication. If this is not possible, tourniquets can be applied immediately after extrication.

However, this contrasts with the recommendations of the Renal Disaster Relief Task Force and the International Search and Rescue Advisory Group, which recommend applying a tourniquet only for life-threatening hemorrhage as a last resort when direct pressure or other hemostatic measures have failed, as tourniquet placement increases the risk of neurological damage, thrombosis, abscesses, blisters, contusions, and abrasions.

They do not recommend tourniquet placement to reduce the risk of crush syndrome if the limb can be saved. If a tourniquet is applied, it should be removed as soon as possible to limit the risk of limb loss.

C'est donc dire qu'il n'existe pas de recommandation claires à ce sujet et que l'utilisation du garrot dans le contexte d'une blessure par écrasement ne devrait pas, jusqu'à nouvel ordre être utilisé de façon systématique.

Source

A. Crush syndrome: a review for prehospital providers and emergency clinicians

Usuda D, Shimozawa, S, Takami, H et al. Journal of Translational

Medicine https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04416-9

B. In adults with suspected crush injury, does the use of tourniquet or

amputation reduce mortality? crush-injury-poster.pdf (rcsed.ac.uk)

C. Crush injury and syndrome: A review for emergency clinicians Brit Long a, ⁎, Stephen Y. Liang b , Michael Gottlieb, Americal Journal of Emergency MEdicine, Crush injury and syndrome: A review for emergency clinicians (binasss.sa.cr)