When every word counts and clarity can make the difference between life and death

It's 2:30 p.m. You're 80 kilometres from the nearest hospital, in a valley where cell service only reaches the ridge. One of your team members just took a serious fall. Suspected open fracture, fluctuating level of consciousness. The radio crackles... you might have one minute to transmit before losing contact.

What do you say first? How do you organize your thoughts when adrenaline kicks in and time is critical?

More than just a radio call

In remote settings, a transmission is never just a single moment. It's a process that evolves, from the initial distress call to the final transfer of responsibility. The information you transmit becomes the vital link between your patient and the advanced care they might receive.

This information travels. It passes from the field responder to the medical coordinator, from the helicopter pilot to the paramedic, from the telemedicine physician to the emergency team. At each step, its quality determines the quality of the decisions that follow.

The challenge? Our contacts don't all speak the same language. The pilot wants to know about site accessibility and weather conditions. The physician focuses on vital signs and symptoms. The evacuation coordinator needs to know what type of transport to prioritize and within what timeframe.

Existing models: useful, but...

Several tools already structure medical transmissions. The SBAR model (Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation) is standard in hospital settings. MIST and ATMIST are popular with ambulance services. ETHANE guides multi-casualty incidents.

These models have proven themselves in their respective contexts. But after years of training guides, forestry workers, and search and rescue teams, one thing became clear: we needed something better adapted to the realities of remote terrain.

Simpler to memorize under stress. More flexible depending on the contact. More intuitive for those without extensive medical training.

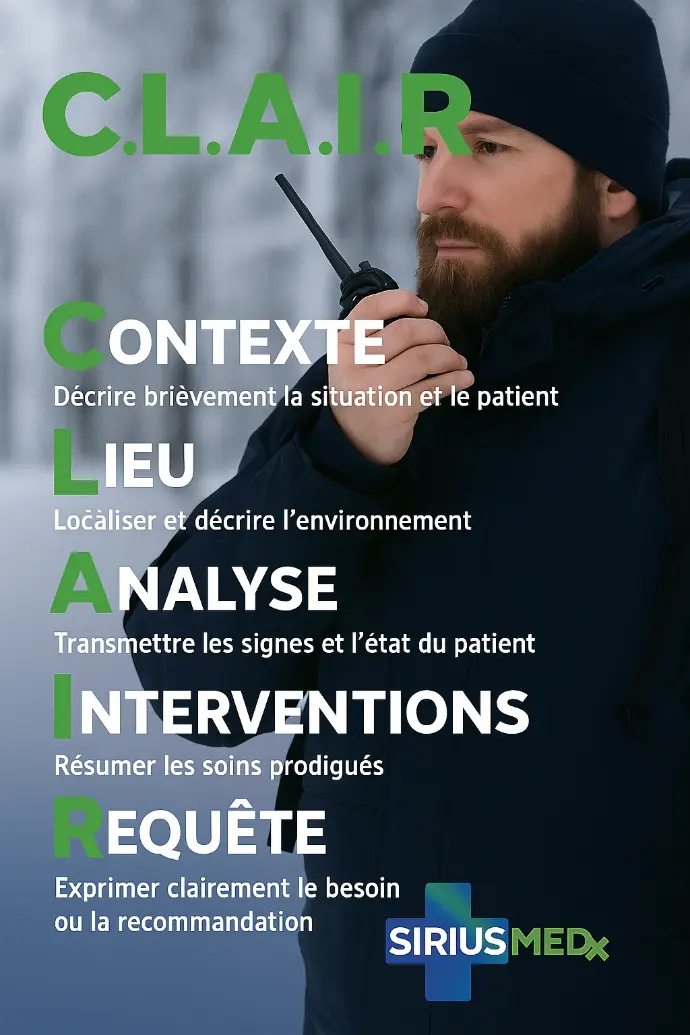

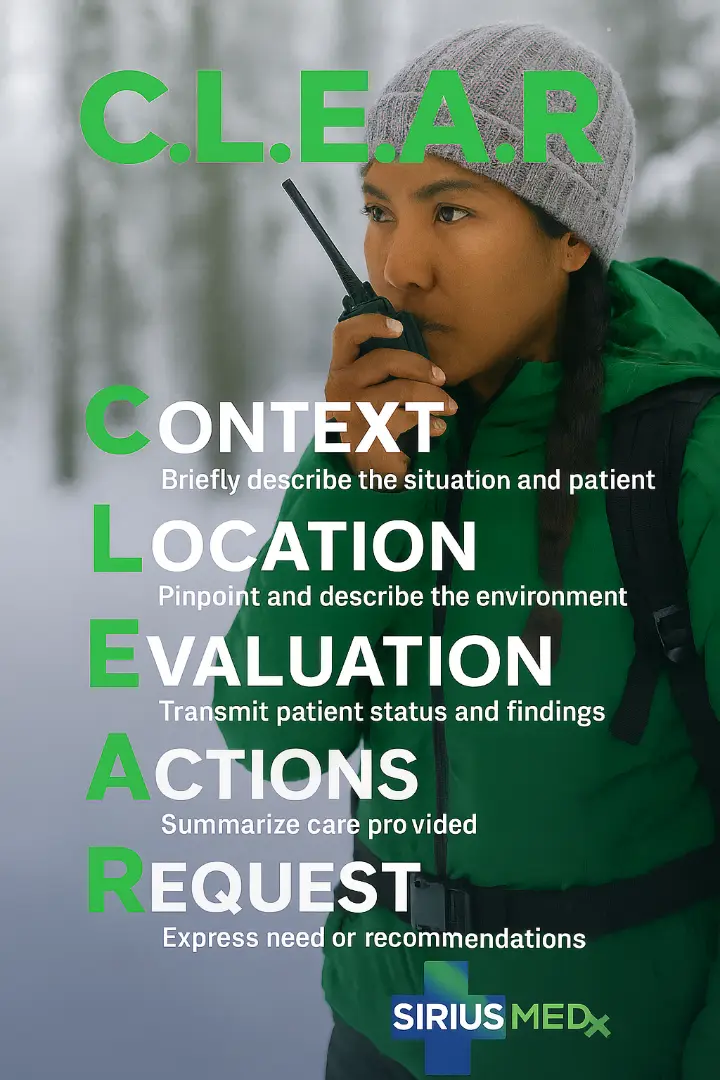

The C.L.E.A.R. model

At SIRIUSMEDx, we developed a model designed specifically for remote interventions. Five letters, five logical steps, a natural progression of information:

This model provides a logical, easy-to-remember framework for transmitting information, with 5 essential elements:

|

C.L.E.A.R. |

Field Objective |

|

|

C |

Context |

Who? What? When? Describe the situation, the patient, and any relevant medical history. |

| L |

Location |

Where? How accessible? Weather and environmental conditions |

|

E |

Evaluation |

Patient status: vital signs, important physical examination findings, symptoms, level of consciousness |

|

A |

Actions |

Actions taken: treatments, medications, stabilization, etc. |

|

R |

Request |

Your request or recommendation: evacuation, monitoring, medical guidance |

C.L.E.A.R. in practice

Let's take a concrete example. You're leading a hiking group when a 55-year-old participant suddenly collapses, complaining of intense chest pain radiating to the left arm.

Unstructured version (unfortunately too common): "Hello? We have a problem here! Someone's having heart trouble I think... It's been hurting for a while... We're somewhere on the trail... We need to do something!"

Context: 55-year-old male, sudden chest pain radiating to left arm for 20 minutes during ascent.

Location: Mont-Albert trail, kilometer 8, ATV accessible, stable weather.

Evaluation: Conscious, pale, diaphoretic, pulse 90 weak, BP not taken, pain 8/10.

Actions: Complete rest, semi-sitting position, ASA given if no allergy.

. Request: Priority evacuation recommended, suspected acute coronary syndrome.

The difference is obvious. In the first case, the contact must ask a series of questions to reconstruct the information. In the second, they immediately have the elements needed to make a decision.

One model, multiple audiences

One advantage of the C.L.E.A.R. model is its adaptability depending on the contact. Facing a pilot, you'll emphasize "L" (location and accessibility). With a physician, the focus will be on "E" (clinical evaluation). For a coordinator, "R" (request) becomes more important.

But the structure remains the same. Information always follows the same logical flow, which facilitates memorization under stress and ensures no essential element is forgotten.

Prepare before you speak

Here's a reality well known to our SAR-TECH colleagues and search and rescue teams: in their semi-annual evaluations, a specific criterion assesses communication quality. Why? Because too often, even experienced responders fail to transmit clear information.

The problem isn't always technical. It's often a matter of mental preparation.

In emergencies, the reflex is to grab the radio immediately and speak. Result: disjointed transmissions, information out of order, sometimes even incomprehensible to the contact.

A few seconds of preparation changes everything:

- Breathe once, deeply. This seems obvious, but adrenaline often makes us forget this fundamental step. Controlled breathing slows heart rate and stabilizes the voice.

- Mentally organize your five C.L.E.A.R. points. Before hitting the button, quickly review: Context, Location, Evaluation, Actions, Request. Don’t have all the answers? Identify what you know for sure.

- Adapt your tone. Clear, calm, composed. A breathless or panicked voice hinders understanding and transmits unnecessary stress to your contact. The physician on call at 3 a.m. needs information, not emotions.

This preparation isn't wasted time. In critical situations, these few seconds invested upfront enable more effective transmission, faster decisions, and ultimately better care for the patient.

More than an acronym

Developing a new transmission model is good. But the issue goes beyond a simple mnemonic tool. It's a question of communication culture.

In remote settings, we don't have the luxury of long, detailed transmissions. We must get to the essentials, structure our thoughts quickly, adapt our language according to context. The C.L.E.A.R. model helps us do this, but it doesn't replace regular practice, realistic simulations, and constructive debriefings.

The forgotten aspect of training

Let's be honest: in our training sessions, what captivates participants most? Making a splint with branches and duct tape. Applying an emergency tourniquet. Suturing a wound. These gestures have something concrete, even spectacular about them. You see, you touch, you measure the result.

Transmission? Less glamorous. Yet how many times have we seen responders perfectly capable of managing a complex fracture become stammering and inaudible the moment they have a radio in their hands?

We must acknowledge a reality: we too often neglect this skill in our training. We address it at the end of scenarios, quickly, almost as a formality. "Okay, now call for help and tell them what's happening." End of exercise.

This is a mistake. In the field, transmission often determines what happens next. Will the pilot agree to take off in this weather? Will the consulting physician authorize evacuation? Will the rescue team understand exactly where to locate you?

Integrate C.L.E.A.R. into all our simulations

Every training scenario should include a transmission component. Not as a separate exercise, but as an integral part of the intervention. Radio in hand, notepad on knee, standing, under pressure.

- During primary assessment: transmission of context and location

- After initial care: update on patient condition and interventions performed

- At the critical moment: request for evacuation or specialized advice

We must create this habit, this automatization. Have our participants leave training naturally thinking: "What am I going to say? How am I going to say it? Who am I going to say it to?"

And above all, we must correct. In debriefing, review unclear transmissions, missing information, ambiguous formulations. With the same rigor we bring to critiquing a poorly applied bandage or deficient immobilization.

Because ultimately, transmitting well is already beginning to provide care. And in remote settings, this skill can make all the difference.

The essential remains essential

Ultimately, C.L.E.A.R. doesn't claim to revolutionize medical communications. Existing models work well in their respective contexts. Our motivation was simpler: create a tool specifically adapted to non-health professionals who intervene in remote settings.

Guides, forestry workers, search and rescue teams, expedition leaders... These responders need a method that's easy to memorize, intuitive to apply under stress, and flexible enough to adapt to different contacts.

Whether you adopt C.L.E.A.R. or any other model matters little. The objective remains the same: transmit essential information in logical order, with clear language, so all responders quickly understand the stakes and make the right decisions.

Because that's what's essential: that information flows effectively to improve patient care.

Key takeaways

- Structured transmission is as important as first aid gestures

- The C.L.E.A.R. model adapts to all remote intervention contexts

- Regular practice and simulations are essential to master the tool

- Each contact has their priorities: adapt your communication without losing structure

Next time you find yourself radio in hand, in a situation requiring rescue, think C.L.E.A.R. This structure could well make the difference.